It was, Bob Woodward recalls, “an almost Shakespearean moment”. He and a Washington Post colleague were interviewing Donald Trump in March 2016. They asked how Trump defines power. The then presidential candidate replied: “Real power is – I don’t even want to use the word – fear.”

Woodward recalls that it was like “Hamlet’s aside, turning to the audience to say: ‘This is what’s really going on, this is what it’s really about. I want it to be known but I don’t want it to be known.’ That great ambivalence of the politician speaking a dangerous truth.”

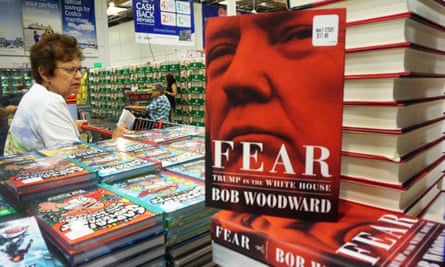

Two and a half years, one presidential election and hundreds of hours of interviews later, Trump’s telling choice of word – fear – was the natural choice of title for Woodward’s latest book, a singularly authoritative portrait of a White House teetering on the edge of a cliff. Whereas other accounts have offered soap opera, this is the presidency as Shakespearean tragedy.

Now 75, Woodward has written about nine US presidents, most famously Richard Nixon. His dogged reporting with Post colleague Carl Bernstein on the Watergate break-in and cover-up, and on Nixon’s dirty tricks and political espionage, played a central part in forcing him to resign – still the only US president to do so – and was immortalised in every journalist’s favourite journalism film, All the President’s Men, starring Robert Redford and Dustin Hoffman.

Woodward came of age in an era of clattering typewriters, cigarette smoke, hot metal, thundering presses and covert calls made from coin-hungry payphones. He still champions shoe-leather journalism and knocking on doors, sometimes late at night, and is not likely to be found dropping snarky comments on Twitter.

A newsman of the old school, he evidently likes to let his reporting do the talking. In an era when the line between news and opinion is increasingly blurred, when even Bernstein offers punditry on CNN, Woodward is perhaps not in his natural habitat touring the TV, radio and podcasting studios being asked to serve up polemical soundbites with viral potential.

Instead, in Fear, he meticulously builds a case against Trump’s fitness for office. He has no need to shout it from the rooftops because the facts are staring us in the face. His body of evidence, charting how decisions get made or don’t in a jaw-droppingly dysfunctional White House, is a welcome antidote to the daily blizzard of online agitprop, rumours and conspiracy theories.

Nearly all his interviews were taped; one ran to 820 pages of transcript; he interviewed one subject nine times. As the 20-month-old Trump presidency already becomes the stuff of history books, Woodward’s contribution carries more weight than the gossipy and sometimes sloppy Fire and Fury by Michael Wolff or the score-settling of Omarosa Manigault Newman’s Unhinged.

Trump has dismissed the book, already in the top of Amazon’s bestsellers of 2018 list, as “a piece of fiction” and used Twitter to brand Woodward “a liar”.

Woodward reflected: “I look at my job as: let’s present the rock solid evidence of what happens. There’s documents, there’s notes, there’s not just the phrase but there’s they sat and they met and this is what happened. Let the political system respond.”

He added: “I just think too many people have lost their perspective and become emotionally unhinged about Trump. I can understand that but that’s not the way the media should respond. The media should respond with what really happened.”

Woodward is full of praise for the “high energy” of many newspapers and TV networks but acknowledges the record was mixed during the 2016 campaign and beyond. “Did we do enough to understand Trump before the election? No. Did I do enough? No. Did we get his tax returns? No. Have we got his tax returns? No. Should we have got his tax returns? Yes. Hard. Yes. The score card coverage of Trump is some real high points and good points by the media and some incomplete.”

Speaking to the Guardian in a glass-walled office at his publisher Simon & Schuster in Manhattan, Woodward speaks deliberately, choosing his words – and his silences – carefully. More guarded with his opinions than other Trump chroniclers, the lack of hyperbole tends to lend him more credence.

He says of the book: “It’s a picture of a White House administration that’s going through a nervous breakdown and, as we know in human terms, nervous breakdowns are not good things. And so it’s a very challenging moment … I would think the most ardent Trump supporter who might read it could not feel comforted.”

How worried should we be that an impulsive narcissist with a childlike understanding of world affairs is in possession of the nuclear codes? Would Trump push the button? “We don’t know the answer to that. There’s a memo which I quote from that the chief of staff – the current one, Gen [John] Kelly – puts out saying no more spur of the moment, seat of the pants decisions; they don’t count. There has to be a formal process and a formal sign-off. That’s the effort to contain some of these impulses.”

Woodward prefers to talk about Trump’s trade war than potential nuclear war, and that prospect is disturbing enough. “What a tariff war can do is substantial and something to worry about and he has those authorities, or he’s claimed those authorities. There’s lots of legal uncertainty about that but I get to talk to the economic gurus in the world at all kinds of levels and this is a real worry: the global order of trade is in jeopardy and things are being done to it that make no sense.”

The book begins with Gary Cohn, then the top economic adviser in the White House, whisking a draft letter that would have terminated the US-South Korea free trade agreement off the Resolute desk in the Oval Office before Trump has a chance to sign it. Later, Trump barks orders to “fucking kill” Syrian leader Bashar al-Assad, but the defence secretary, Jim Mattis, quietly disobeys. Kelly is quoted as saying of Trump: “He’s an idiot. It’s pointless to try to convince him of anything. He’s gone off the rails. We’re in Crazytown.” Kelly has denied the comment.

Intriguingly, some prominent voices in the book scorn the theory that the Trump campaign colluded with Russia during the 2016 presidential election. Among them is the president’s former lawyer John Dowd, although even he came to regard Trump as “a fucking liar”, it records. Did Woodward himself find any explanation for the very strange relationship between Trump and Russian president Vladimir Putin?

“No, not really. I’ve obviously looked. But here’s the reporting lesson from this, from doing this for 47 years at the Post. You’ve got to go to the scene. You’ve got to show up and, if you’re really going to do the Russian investigation, I’d move to Moscow. You know, I’d probably be shot or arrested. But the answer is in Russia.

“I think that’s the hardest of targets but that’s that’s what you would do. If I were 30 and unmarried without children and had some way – I don’t know how you would do it. I’ve asked people and they’ve laughed and said you can’t. But ultimately the answer is in Moscow and St Petersburg.”

Even if special counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation comes up with definitive proof of collusion, it is uncertain in the present hyperpartisan climate (“Polarisation is not the right word. It’s political war, unfortunately”) whether his findings will be accepted as the last word. Woodward continues: “It depends on the quality of the report. In Watergate, one of the great lessons for me personally was you need a storytelling witness; you can’t just say: ‘I overheard’ or ‘I speculated’.

“John Dean, Nixon’s counsel, testified before the Senate Watergate committee on live national television: it was on every network, gavel to gavel coverage for four days. ‘I met with Nixon. He said, how much do we need to pay to silence the burglars? What about this? What about that?’ And it was devastating. Then you had the second punch which was the tapes which validated it, made Nixon his own narrator. So I’m not sure whether that’s going to happen.”

Woodward will forever be associated with Watergate and, like Paul McCartney, seems to be at peace when asked to replay his greatest hits. The parallels with that drama have been inescapable and grown ever more acute since Trump took office. Mueller’s investigation was triggered by a break-in at the Democratic National Committee, this time in digital form. Trump fired his acting attorney general and FBI director, just as Nixon first ordered his attorney general, and then the deputy, to fire the Watergate special prosecutor; they refused and quit on what became known as the Saturday Night Massacre. Trump, like Nixon before him, has gone to war against the media and displayed paranoia about perceived enemies.

This may prove a rare instance where history does not merely rhyme but does in fact repeat itself. But for now there is at least one departure point, according to Woodward. “Nixon was a criminal and a well-documented criminal. In the Mueller investigation, we don’t know whether Trump was or is, and that’s a big difference.”

In the 1970s there also was no social media, no presidential Twitter account and no Fox News working around the clock to discredit Trump’s critics. “Back in Watergate, Fox News was implanted in the White House,” Woodward continues. “One interesting continuity line here was Roger Ailes, who was a Nixon media adviser [and later chief executive of Fox News].

“I remember Ron Ziegler [Nixon’s press secretary] calling us ‘character assassins’. Trump and these people have said lots of things; I haven’t heard character assassin. That’s bracing. I was 29 when that happened. You see the leader of the free world’s spokesman up there saying you’re a character assassin. So you have to be deeply concerned because I’ve seen these things. The system can work in the end, whatever that end might be.”

Woodward ultimately retains faith that it will work. “I’m from the midwest and you can’t discard the kind of traditional optimism that you have.”

Nixon and Trump would be two extraordinary bookends to any journalistic career but Woodward shows no sign of letting up. He finds the energy in Washington reminiscent of when he first moved there at the start of the 1970s, serving in the navy, living in a one-bedroom apartment and subscribing to the Post. More than four decades later he is still knocking on doors, still seeking the next “Deep Throat”, his shadowy Watergate source later revealed to be Mark Felt, second in command of the FBI.

Are there Deep Throats out there in the Trump era? “Many,” he says confidently. “We’re looking for more. Never enough.”