Image: Angelica Alzona

The Women’s Health Center in Charleston, West Virginia is an unassuming, single-story beige brick building in a shabby neighborhood, just steps from the train tracks and a crisis pregnancy center, a shuttered vape shop, and a row of small homes surrounded by chainlink fences. I visited the center, the last abortion clinic in the state, on a Wednesday in June, one of the two days each week that the clinic performs abortions. Christopher McComas, 52, stood by the entrance to the clinic’s parking lot, equipped with a cell phone that he trained at everyone who approached the clinic.

“Hey brother, can I talk to you for a second? Please, for a second? Do you think it’s going to be a boy or a girl? Does it have blue eyes, or maybe brown eyes?” McComas yelled at one couple, a tall photo of a blood-covered fetus propped up by his side. “God loves you, please don’t do this ma’am! I beg you not to do this! It could be a boy or a girl,” he continued to yell at the couple as they entered the clinic, shielded by a large umbrella held by a clinic escort. “It could have brown hair!”

McComas has been coming since January, harassing the clinic’s patients and staff while live-streaming his protests on Facebook, often tagging them with the line, “live at the only murder mill in West Virginia.” I got a small taste of McComas’s tactics when I approached him. I had barely introduced myself as a reporter, putting out my hand to shake his, when he pulled out his smartphone and pointed it at my face.

“You just walked up and you engaged with me without me allowing you to, within eight feet and a hundred foot of the door,” he said, arguing that I had violated a recently enacted ordinance meant to protect the Women’s Health Center. At the end of May, Charleston’s city council passed an ordinance forbidding people from blocking the entrance or exit of a healthcare facility as well as coming within eight feet of a patient entering the building without the person’s consent. But the ordinance has not stopped McComas and a small group of his fellow protesters; if anything, it’s only heightened their sense that they are martyrs fighting a righteous war.

“You reached out your hand within two feet of me, right? Well, the cameras aren’t lying, I’m gonna call them on you right now,” he said, referring to the police. “We rebuke the spirit of Jezebel in the name of Jesus! We’re not going to have it!” he bellowed as I walked away, shaken by the encounter. Someone watching the live stream did eventually call the police. More than an hour later, a few cops showed up, handed McComas a copy of the ordinance, and left.

The people who make it to the clinic are the lucky ones

But by then, I was sitting inside the clinic, watching McComas and the small group of activists who had joined him on the small screen of my cell phone. The room, decorated with outdated furniture made sometime in the 1980s, was quiet, the only noise was coming from the television mounted on the wall. As people walked into the waiting room through the back entrance—no one uses the main entrance anymore, not since the protesters arrived—some, like a teenager and her mother, looked rattled.

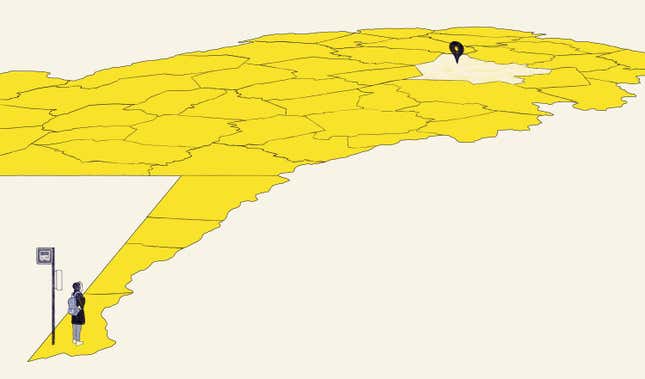

The people who make it to the clinic are the lucky ones. Getting an appointment for an abortion at Women’s Health Center requires a tricky alignment of circumstances: First, a patient must be early in their pregnancy, as the clinic has a cut-off date of 16 weeks (the state instituted a 20-week ban in 2015). Then after securing an appointment, a patient must listen to a mandated script that includes biased information, among other deterrents, about the potential health risks of an abortion. The patient is also reminded that the father would be legally obligated to pay child support. After that, the patient must wait at least 24 hours to fulfill the legally mandated waiting period.

Even this series of events presupposes that one has the money for the procedure, which costs on average about $450, and the ability to get to the clinic, which can often depend on a complicated matrix of questions: How far do you live from the clinic? Do you have a car? Can you pay for that tank of gas? Are you able to take time off from work? Can you afford to miss that shift? If you have children, can someone take care of them? The answers to these questions became even more complicated in November of last year after voters narrowly passed Amendment One, a constitutional amendment that barred the state’s Medicaid program from funding abortions except in cases of rape, incest, or when the person’s life is at risk. It is particularly onerous for West Virginians, where almost one out of every three people are on Medicaid.

Then there’s the crisis pregnancy center next door to the clinic, confusingly named Woman’s Choice. So many patients have mistakenly gone to the deceptively named crisis pregnancy center that the Women’s Health Center put up a prominent sign in its parking lot telling people that it is not affiliated with the center. (Its proximity to the abortion clinic “may be a coincidence or it may not,” its then-director said coyly when it opened in 2013, taking over a space that formerly housed a gay bar.)

But it wasn’t always this way. “Primarily it was, could you get to a clinic? Could you afford the abortion right now?” Sharon Lewis, the director of the Women’s Health Center, told me of previous decades when the state had more abortion providers and far fewer restrictions. Lewis, a regal-looking black woman with close-cropped salt-and-pepper hair and a steely if beleaguered air, has been the director of the clinic since 1998; her office door is plastered with newspaper cartoons that point out the hypocrisy of the anti-abortion movement. “What it’s become more and more is, where can I go? How can I afford to get there? They’re making it much more difficult for women to even keep an appointment. They have to go two or three or four times, and that’s by design.”

Leo Brancazio, who recently returned to his home state to lead the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at West Virginia University, was disturbed by how much had changed since he had left. “In the 14 years I was gone,” Brancazio told me, West Virginia “went from a progressive state to one of the more regressive states in terms of healthcare for women.”

The backward slide that’s made Women’s Health Center the last clinic is the result of a confluence of factors that have made it increasingly difficult for people to legally terminate a pregnancy, not just in West Virginia but in states around the country. West Virginia’s conservative legislature, with the support of many of the state’s Democrats, makes it just difficult enough to get an abortion or run a clinic. The owner of a for-profit clinic shuts its doors, deciding it’s too difficult to run a clinic in a hostile state. Right-wing Christian protesters, riding a wave of momentum, decide to again start picketing. Even as solidly blue states are belatedly codifying and expanding abortion access, more find themselves in a situation where decades of right-wing anti-abortion campaigning have created an environment where, given the right set of circumstances, their state could—like West Virginia, or Kentucky, or Missouri—tip over that tenuous line.

The dwindling number of clinics in West Virginia as well as in bordering states like Kentucky, which also has only one abortion clinic, has forced people throughout the region to go to even greater lengths to obtain an abortion. The Women’s Health Center sees a “significant number” of patients from Ohio as well as Kentucky, according to Katie Quinonez, the clinic’s development director; one former abortion provider in the state estimated that 30 to 40 percent of his patients had come from outside of West Virginia. And given the Women’s Health Center’s early 16-week cutoff date, even someone who lives in Charleston may need to go outside of the state to get a legal, elective abortion.

“Depending on how far along they are, it might mean the best clinic for them isn’t the one that’s closest, but the one that’s an hour or two further away,” Caitlin Gaffin, one of the co-founders of Holler Health Justice, said. Founded by Gaffin and Chela Barajas at the end of 2018, Holler Health Justice is a volunteer-run abortion fund that provides everything from practical support—like advice on car rides and plane tickets—to a herculean amount of coordination to ensure people make it to their appointments.

Providing this kind of support in an overwhelmingly rural, mountainous state like West Virginia can be logistically challenging. One woman they assisted lived on a mountain without consistent cell phone service. “We couldn’t even call her because she had to go to the top of the mountain to get a cell phone signal,” Gaffin recalled. “She was in this remote area of the state, and she didn’t know a soul who even had a driver’s license.” A volunteer ended up driving to her small town and then taking her to and from Louisville, Kentucky, where she had her appointment. In the case of another West Virginia woman whose appointment was also in Louisville, Holler Health Justice paid for her to take two flights to get to Charleston; from there, Barajas drove her two hours to meet a volunteer from a different abortion fund, who then drove her the rest of the way to Louisville. Each leg of her trip took several days. “There’s always a new set of challenges,” Gaffin said.

When Gaffin was a student, she had two abortions, both of which were covered by Medicaid. “That’s what scary,” she said. “I try to think now, post-Amendment One, what would I have done. And I know that I would’ve done something. I probably would have been able to piece together the money, but I know there are other points in my life where $500 would not have been an option.” Money, or the lack of it, is a constant worry that she and Barajas hear from the people who, as Barajas put it, slide into their DMs. “So often, it’s, ‘I have nothing right now but I’ll be paid on Friday, but I’ll only have $30 extra from that,’” Gaffin said. One woman had sold her television and other small household items and still needed $300 more to pay for her abortion; she told Gaffin she was considering selling plasma because she had nothing else left to sell.

One woman had sold her television and other small household items and still needed $300 more to pay for her abortion; she was considering selling plasma because she had nothing else left to sell

Lewis understands the stakes. One day, when she was a young girl rollerskating with friends, a friend told her of a mother who had been jailed because she performed an abortion. This was before Roe, and the story stuck with her. She sees all of the attacks on her clinic—the protesters, the passage of Amendment One—as part of a concerted, nationwide effort to gut abortion access and roll back the rights that were once fundamentally, if imperfectly, guaranteed by Roe.

“In this country, you have a right to decide what you want to do with your body, but your religion or your philosophy doesn’t extend to mine,” Lewis said. “At least, that’s the way it should be. But that’s not the way it is right now.”

As a 16-year-old in 1972, two years before Roe was decided, Maggie McCabe traveled from West Virginia to Washington D.C. to get an abortion. “I found out on a Friday that I was pregnant,” McCabe, now 63, recalled. “And on Sunday, mother and I were on a plane to D.C.” It was McCabe’s experience that inspired her mother, Jane McCabe, to work with Planned Parenthood as well as social justice-minded churches and pastors to open the clinic that would become the Women’s Health Center. “She was outraged at the process, of having to go out of state. She also wanted a place not only for abortions, but a women’s health center for low-income women,” McCabe told me.

One of a number of explicitly feminist, mission-driven abortion clinics that opened in the wake of Roe, the Women’s Health Center wasn’t always the only option for people seeking an abortion in the state. In 1976, the year the non-profit clinic opened, another private clinic also opened in Wheeling, close to the state’s eastern border with Pennsylvania and operated by doctors from Toledo, Ohio. Roe ushered in a new era: People living in states where abortions had been illegal soon had multiple legal options to terminate their pregnancies, from clinics to hospitals to private practices. At times, providers had to be forced to offer abortions—a lawsuit eventually compelled several of West Virginia’s hospitals to offer abortions—and protests, led by Catholic activists, were common. But by 1977, the Women’s Health Center, the clinic in Wheeling, and several hospitals in the state were performing almost 60 abortions per week, according to a newspaper account from the time. By 1981, according to the Guttmacher Institute, there were 11 abortion providers in West Virginia, a mix of clinics, doctor’s offices, and hospitals that performed the procedure.

But that number soon began dropping across the United States, as violent anti-abortion extremists, starting in the latter part of the ’80s, began targeting clinics and killing abortion doctors. In response, more and more hospitals and private practitioners stopped providing abortions, making abortion primarily the domain instead of clinics like the Women’s Health Center. The private clinic in Wheeling closed in 1988, and by 1999, mirroring national trends, the number of abortion providers in West Virginia had dropped to three. The state’s hospitals, like many around the country, largely stopped providing abortions except those that were deemed medically necessary. As Time wrote in 2013, “political pressure and the promise of funding has been a powerful tool in preventing hospitals from performing abortions.”

After the Kanawha Surgicenter, a private, for-profit clinic located in Charleston shut its doors in January of 2017, the Women’s Health Center became the last clinic in the state. Gorli Harish, the Kanawha’s former owner, moved to California, where he continues to be an abortion provider. “The starkest contrast comes when somebody is a minor,” Harish said of the two state’s abortion laws. In West Virginia, a parent needs to be notified at least 24 hours before a teenager under the age of 18 can get an abortion, and in 2017, the state made it more difficult for young people to get around the parental notification requirement. “But here,” he said of California, “they come and ask for an abortion, they get an abortion, no questions asked.” The difference, Harish said, is “like night and day.”

During her 30-year tenure at Women’s Health Center, Lewis has seen an intense escalation of the anti-abortion movement. In 1990, the notorious anti-abortion extremist James “Atomic Dog” Kopp and a group of Catholic college students affiliated with Operation Rescue chained themselves together inside the clinic. Kopp would later be convicted for shooting and killing abortion provider Barnett Slepian, a doctor in Buffalo, New York, in 1998. In 1999, Clayton Waagner, a member of the extremist group Army of God, stalked a nurse at the Women’s Health Center with the intent to shoot and kill her. It was part of his years-long terrorist campaign against abortion providers. After being suspected of sending letters that he claimed contained anthrax to hundreds of clinics around the country, he was placed on the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted list. He was eventually captured in 2001 at an Ohio Kinko’s, where he was about to fax bomb threats to a number of clinics. Waagner was convicted on dozens of federal counts and remains in federal prison today.

The recent protests at the Women’s Health Center, first organized by Derrick Evans, an attention-hungry anti-abortion activist who began livestreaming the protests on his Facebook page, are part of a nationwide uptick of harassment at abortion clinics. While it’s unclear why they began organizing, clinic staff speculated that it’s partly due to the passage of the Reproductive Health Act in New York state. “They are misogynists, they’re racists, they’re homophobes. They’re just the ultimate bigots,” Lewis said bluntly of the protesters. She remembered one particularly unsettling moment during one of Evans’s early protests: “He’s livestreaming his conversation with this other friend of his who is saying, ‘I’m on my way. I’m bringing my 9mm [gun].’”

The threats and protests have rattled patients, some of whom have told the clinic staff that they’re scared to return to the clinic because friends and family had seen them in the group’s Facebook videos. In response, the clinic has put up a fence surrounding their parking lot and has begun regularly organizing volunteers to serve as clinic escorts, who don bright pink vests and carry umbrellas to shield the faces of people who come to the clinic from prying eyes. The clinic escorts themselves have been targeted—in May, Jamie Miller, a volunteer clinic escort, filed a restraining order against Evans, which he violated by continuing to show up at the clinic. (At the end of July, a month after I visited the Women’s Health Center, McComas was arrested on misdemeanor charges of disorderly conduct and assault after he allegedly threatened an 82-year-old volunteer clinic escort; those charges were later dismissed.)

I have two granddaughters, and I don’t want them to have to fight this fight

I met with McCabe, who is now a clinic escort at the Women’s Health Center, fresh after a shift, an enamel pin she bought from Etsy that says “clinic escort” attached to the lapel of her purple polo shirt. “I was escorting someone and with another escort, and [McComas] started harassing me about being a grandmother,” McCabe said. “And how could I allow people to murder their children when I’m a grandmother myself? And the escort that was with me had to stop me from going and just laying into him, physically.”

McCabe has the demeanor of a bulldog, and cheerfully described herself as an “outright bitch.” “I’m a parent. I’m a mother, and I’m a grandmother. But that was my choice to be a mother,” McCabe added. “I have two granddaughters, and I don’t want them to have to fight this fight. I don’t want them to have to go out of state. I don’t want them to have to take a hanger or beat their stomach until they self-abort. I don’t want them to die from sepsis from an illegal abortion.”

The protesters reserve their most targeted vitriol for Lewis, but little fazes her any more. “Particularly the clinic directors, most of us have been in it for the long haul. It’s something that you deal with,” Lewis said. Still, she showed me a meme she keeps on her computer—a young boy screaming with his hands over his ears. “This just about says it all,” she said wryly.

In 2013, at the height of the national furor over the abortion doctor Kermit Gosnell, Itai Gravely, a woman working with the right-wing Alliance Defending Freedom and the Family Policy Council of West Virginia sued the clinic, alleging that a Women’s Health Center doctor had botched her abortion the year prior. Gravely had based her claim on the word of Dr. Byron Calhoun, an anti-abortion physician who had operated on her after her abortion. Calhoun is also the vice-chairman of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the Charleston branch of West Virginia University’s School of Medicine, and the medical adviser for the anti-abortion National Institute of Family and Life Advocates. He falsely told Gravely that the skull of the fetus had been left inside her uterus, and then referred her to a lawyer at the Family Policy Council.

The judge overseeing the lawsuit ultimately dismissed it, calling the claims “immaterial and, frankly, sensational,” but by that point, the state’s Republican attorney general Patrick Morrisey had already seized on the lawsuit as an excuse to scrutinize the Women’s Health Center. Calhoun wrote a letter spurring Morrisey to action. “We commonly (I personally probably at least weekly) see patients at Women’s and Children’s Hospital with complications from abortions at these centers in Charleston: so much for ‘safe and legal,’” Calhoun wrote. His claims were later shown to be lies.

“He had no consequences for the dishonesty that he fabricated in the fabricated lawsuit that he crafted with the anti-choice head of the Family Policy Council,” Lewis said of Calhoun. “He just tells lies, and he still works there for WVU and for CAMC.”

The constant effort to protect abortion access is “frustrating because it should be settled,” Lewis said. “The fallacy in the settled law is that the Supreme Court allows states to impose restrictions”—she was referring to the 1992 Supreme Court decision in Planned Parenthood v. Casey—“and that’s why we’re seeing all of these ridiculous anti-abortion laws right now.”

If Casey opened the door to abortion restrictions, then the Republican takeover of the West Virginia legislature in 2014—for the first time in 84 years, they controlled both chambers—kicked it clean off its hinges. But it’s not as though the state’s Democrats are particularly supportive of abortion rights. Joe Manchin, the former governor and now senator, is notoriously, to use his own terminology, “pro-life.” Democrats in the state legislature, many of whom are anti-abortion, regularly vote with their Republican counterparts in favor of abortion restrictions. While the state party platform once stated that “we stand proudly for a woman’s right to choose,” the current platform makes no explicit mention of abortion. Still, until 2014, the most severe anti-abortion restriction passed in the state was an informed consent law in 2003, which mandated a 24-hour waiting period and the printing of state-sponsored abortion counseling materials that claim, outlandishly and contrary to widely accepted studies, that the “possible psychological effects of abortion” include everything from developing an eating disorder to drug abuse to sexual dysfunction. (The estimated cost, at the time, of printing the booklet was $250,000 per year; that same year, only slightly less than the state’s Medicaid program spent on abortions.)

“When the Democrats were in control, they pushed forward anti-abortion legislation also. But it didn’t have significant ramifications for access,” Margaret Chapman Pomponio, the head of West Virginia Free, the state’s largest reproductive justice group, told me as we sat in her office located in a YMCA in downtown Charleston. The night before, the group had hosted an open house; cardboard cutouts of Michelle Obama and Samantha Bee still nestled in a corner. “When it shifted, they started going hard on some of the most restrictive bills in the country.”

With an overwhelming majority, Republicans quickly moved to pass a series of more draconian anti-abortion restrictions—in 2015, the legislature passed the 20-week ban, and a year later, lawmakers passed a ban on the dilation and extraction abortion method, the most common and safest way to abort in the second trimester, overriding the Democratic governor’s veto. “Now we have to do amniocentesis and inject medicine into the fetus to stop their hearts before we can proceed,” WVU’s Brancazio said of the ban’s impact on the university hospital. “And that absolutely adds nothing to the procedure and actually increases the risk to the woman a little bit, but we have to, by law.” In 2017, the state passed a parental consent law and a ban on telemedicine medical abortions, a move that preempts providers from expanding the services they offer before they can even begin. “It’s that chipping away at access that continues year after year after year,” Lewis said.

Then came Amendment One, a constitutional amendment that the legislature put in front of voters in 2018. Voters narrowly approved the No Right to Abortion Amendment, adding a line to the state’s constitution stating that “nothing in the Constitution of West Virginia secures or protects a right to abortion or requires the funding of abortion.” After the state expanded Medicaid in 2014, the number of abortions paid for using the federal dollars jumped dramatically. That alarmed anti-abortion elected officials who introduced Amendment One. It takes aim at both Medicaid funding for abortions and setting the groundwork for a potential post-Roe future. As the state’s chapter of the ACLU put it, the amendment was “the most extreme attack on women’s reproductive rights in West Virginia history.”

On the surface, it would seem that most West Virginians would be supportive of restricting abortion access. According to a Pew poll from 2014, 58 percent of adults in West Virginia believe that abortion should be illegal in almost all or all cases. This is a poll that is widely cited by anti-abortion activists in the state, yet as researcher Tresa Undem has pointed out, even those who believe that abortion should be almost universally banned can tend to hold contradictory views. As Undem put it, “when collapsed into two categories—legal and illegal—you tend to get a divided public.” That seems to be the case in West Virginia. In the beginning of 2018, and before Amendment One was on the ballot, West Virginia Free, the Women’s Health Center, and other organizations had commissioned a poll by Hart Research that found that 54 percent of likely voters in the state did not want the legislature to ban Medicaid funding for abortion; 62 percent of people who were personally opposed to abortions believed the government should not have a say in abortion decisions.

“We find time and time again that people actually support the right to abortion. But if you ask people, ‘Are you pro-life or pro-choice?’ they’re going to say they’re pro-life,” Pomponio said. “But [..] it’s clear that people actually don’t want the government in charge. They may personally oppose abortion but they don’t want to decide for their neighbors or family members.”

Pomponio initially believed Amendment One was too radical to be approved by voters. “If this goes to the ballot box, there is no way this will pass,” she remembered thinking. “We knew from polling that it was going to be tight. But we did believe that we could win.” West Virginia Free, along with the Women’s Health Center, the state’s ACLU chapter, and Planned Parenthood South Atlantic mounted a grassroots campaign in the months leading up to the November elections, but they were drastically outspent by anti-abortion groups like Susan B. Anthony List, which poured $500,000 into the state to pass Amendment One. West Virginians for Life framed Amendment One as a “taxpayers’ rights” issue and a “yes” vote as ending “taxpayer-funding of abortion on demand.” Amendment One ultimately passed by fewer than four percentage points. “If we had had the resources to be truly statewide and in all of the media markets, we totally would have won,” Pomponio said. “There was, not surprisingly, a misinformation campaign going on the other side. And they poured a lot of money in at the last minute.”

For Wanda Franz, the president of West Virginians for Life, the fact that Amendment One laid the groundwork for a future in which Roe is overturned was a “secondary factor;” the primary goal, she said, was to end Medicaid funding for abortions. “What we have now in West Virginia is at least protection against future nutty Supreme Court people trying to impose abortion on the people of the state without running it through the legislature,” she told me one afternoon, blinking owlishly at me through her glasses, as we sat in her office in Morgantown, a converted single-family home across the street from a small cemetery.

Until 2011, Franz was the head of the National Right to Life Committee, one of the nation’s leading anti-abortion groups and the crafter of anti-abortion model legislation that has passed in several states around the country, including in West Virginia. Franz, who describes abortion as the “ultimate form of self-inflicted dehumanization” and a “self-inflicted holocaust,” has a tendency to casually throw out dubious claims about abortion that are not backed by reputable research—that getting an abortion leads to breast cancer, that people who end their pregnancies will, as she put it to me, “have severe long-lasting psychological problems.” Despite this, both Franz and her organization are regularly courted by Republican officials. At one point as we were speaking, the Republican candidate for governor Woody Thrasher and a perky young aide bounded through the door to meet with Franz.

Franz is an adherent of the view that rather than push to overturn Roe by introducing near-total bans on abortion with the intention of going all the way up to the Supreme Court, it’s more effective to kill Roe by a thousand implementable cuts. According to experts, this strategy has been more effective and thus more dangerous. “It’s going to take the states putting controls on abortion,” she said, adding, “I’m not interested in spending time working on a bill that is going to be enjoined for sure and not go into effect.”

Pomponio, for her part, believes that the passage of Amendment One—as well as the near-total bans on abortion that have passed in other states—has galvanized pro-abortion activists in West Virginia. The Women’s Health Center has seen an influx of people volunteering to be clinic escorts, and the night before we met, West Virginia Free had held an unusually well-attended open house at their office, where supporters decorated printed out images of uteruses with glitter. “I didn’t know most of the people in the room. It was wild,” she said. “I was like, ‘Well, where are the usual suspects? I see a lot of new energy.”

She believes that Amendment One’s narrow victory spooked the state’s Republicans. “They had kind of an ‘oh shit’ moment when they saw how narrow it was,” Pomponio said. “They lost people. There were more progressives coming in than we’ve seen in ages.” Still, the passage of Amendment One is a huge loss. “Our constitution, prior to the passage of Amendment One, provided a greater right to health and safety than the federal constitution,” Pomponio said. “But there’s so much intergenerational poverty and so many other issues that have bubbled up, and we’ve turned red, and we’re in a new landscape.”

On my last day in West Virginia, I went back to the Women’s Health Center. It was a Friday, not one of the days the clinic performs abortions, yet a small group of anti-abortion activists was set up outside the clinic’s door, including one woman with her young child. She encouraged me to take some leaflets, many of which seemed to come from the crisis pregnancy center next door.

The climate here means that, whether abortion is legal in certain ways or not, it’s still so unattainable to so many people

I left the Women’s Health Center thinking about its future and the future of clinics like it; clinics whose origins spring from a feminist commitment to abortion, and the recognition that all people who wish to end their pregnancies should be able to do so; clinics that survive even under the immense weight of legislative pressure. The neverending stream of protestors, the withdrawal of hospitals and private doctors from the business of abortion provision, all of these factors swirl together to create a precarious situation, for both the Women’s Health Center and the women of West Virginia.

Before Roe, a group of obstetrics and gynecology professors wrote that “independent clinics will probably not be necessary if all hospitals cooperate in handling their proportionate share of these cases.” That was, it turns out, an optimistic assessment. As Eyal Press put it in his book Absolute Conviction, today’s reliance on mission-driven clinics has isolated “abortion from the rest of mainstream medicine.” “Suppose a woman went to a hospital for an abortion. How would anybody on the outside know?” Press asked. But, he wrote, “There was no such ambiguity about the patients who showed up at [abortion clinics].”

This is an unsustainable situation—but there are some signs in the state that it’s beginning to change. Even before the passage of Amendment One, WVU’s Brancazio and other doctors had realized there was a dire need to expand abortion access in the state. When we spoke this past June, Brancazio said the university hospital in Morgantown has recently begun providing a small number of elective, medical abortions in the first trimester, and the department is in the process of applying for funding to provide more abortion training to residents. “These are some very slow baby steps that we’re doing,” Brancazio said, adding, “We have to make sure that we don’t, excuse my language, piss off the legislature so they don’t cut our funding. We’re walking a little bit of a tightrope.” He said more and more residents are interested in getting abortion training. “The younger generation of doctors coming on really understand the need for this,” Brancazio said. “For a while, ob/gyns were a little asleep on this issue, and things got out of hand. Now, we’re taking the horns again.”

“The climate here means that, whether abortion is legal in certain ways or not, it’s still so unattainable to so many people,” Holler Health Justice’s Gaffin told me. “Whether Roe exists or not, it doesn’t really impact the work we’re doing. We’re still going to be doing the same work.”

She added, “There’s still going to be the same need for us.”